An amazing exercise in developing wordly intuition based on realism.

Vaclav Smil wields numbers to paint a very interesting picture to help us understand how the world as we know it is able to keep on running like it is doing. I found this exercise very insightful. Maybe the most ground-shaking idea that I gained from this book, was the sense of how dependent the world still is on fossil fuels. There are so many processes behind the functioning of our world, that are nearly impossible or at least very difficult to transition to sustainable forms of energy. Erecting wind turbines and keeping them running inherently uses fossil fuels, for example. Planes, container ships, plastics, steel; staples of our society, are all virtually infeasible without fossil fuels. At times it is depressing to realize how difficult of a task it is to guide humanity to a sustainable balance with the planet. But it is irrefutably important to gain this knowledge, because reasoning from a more realistically grounded view of world will allow us to better attack these challenges.

This work reminds me of the field of progress studies, to which I was first introduced by Jason Crawford from The Roots of Progress.

The book with seventy-one short essays (part of them republished, part of them appearing in print for the first time) is split up in seven broad themes. Let me just go over them in order, noting down interesting tidbits along the way.

People

Among the things discussed here, are indicators of quality of life. Vaclav proposes infant mortality, because low rates are impossible to achieve without a combination of critical factors that define quality of life—good healthcare, proper maternal and infant nutrition, sanitary living conditions, social support for disadvantaged families. Infant immortality thus becomes a single variable that captures something that others have devised complex multi-variable systems for.

People all over the world grow taller because of better health and nutrition (The Netherlands still practically tops the charts for tallest citizens). This might be attributed to the role of milk consumption during childhood.

Humans are monsters of sweating. We can sweat the most, and our bodies do not require the deficit to be made up instantly. By being able to heavily regulate our bodily temperature, humans can outlast antelopes, deer, and kangaroos.

Megacities have more than ten million people living in them. And there are an increasing number of them in our world, as the ultimate symbol of the shift from countryside to urban living. It also perfectly illustrates the receding influence of Western countries and the rise of Asian countries. More than sixty percent of the megacties are in Asia. African megacities like Lagos and Kinshasa are embodiments of disorganization and environmental decay. Water and air quality in Chinese megacities is bad. Murder rate in Rio de Janeiro approaches 40 per 100,000. Cities continue to attract new people.

Countries

The United States isn't all that exceptional as people might fantasize. Europe's decades of peace and prosperity are to be appreciated. Japan seems to be on a decline.

[Japan's] swift post–Second World War ascent ended in the late 1980s, and it’s been downhill ever since: in a single lifetime, from misery to an admired—and feared—economic superpower, then on to the stagnation and retreat of an aging society. The Japanese government has been trying to find some way out—but radical reforms are not easy in a gerrymandered country that still cannot seriously contemplate even moderate-scale immigration and that is yet to make real peace with its neighbors.

China's rise has been swift and threatening for the Western world, but it seems to be headed in a similar direction as Japan. India might become the new China, so to say. Its population will soon surpass China's.

Machines, designs, devices

The 1880s brought forth many modern inventions.

The 1880s were miraculous; they gave us such disparate contributions as antiperspirants, inexpensive lights, reliable elevators, and the theory of electromagnetism—although most people lost in their ephemeral tweets and in Facebook gossip are not even remotely aware of the true scope of this quotidian debt.

Electric motors power modern civilization; from tiny DC devices used for smartphone vibrations (with power requirements at a small fraction of a watt), to motors powering the TGV (6.5 to 12.2 megawatt), and stationary motors for power compressors, fans, and conveyors (exceeding 60 megawatts).

Diesel engines are pretty efficient and they find their use mostly as enablers of massively centralized industrial production and irreplaceable prime movers of globalization.

Diesels power virtually all container ships and all carriers of vehicles and bulk commodities such as oil, liquefied natural gas, ores, cement, fertilizers, and grain. They also power nearly all trucks and freight trains. Most of the items that readers of this book eat or wear are transported at least once, and usually many times, by diesel-powered machines, often from other continents: clothes from Bangladesh, oranges from South Africa, crude oil from the Middle East, bauxite from Jamaica, cars from Japan, computers from China. Without the low operating costs, high efficiency, high reliability, and great durability of diesel engines, it would have been impossible to reach the extent of globalization that now defines the modern economy. Over more than a century of use, diesel engines have increased both in capacity and efficiency. The largest machines in shipping are now rated at more than 81 megawatts (109,000 horsepower), and their top net efficiency is just above 50 percent—better than that of gas turbines, which are at about 40 percent. And diesel engines are here to stay. There are no readily available mass-mover alternatives that could keep integrating the global economy as affordably, efficiently, and reliably as Diesel’s machines.

Fuels and electricity

In 1971, Glenn Seaborg, a Nobelist and the then-chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, predicted that nuclear reactors would generate nearly all the world’s electricity by 2000. Seaborg envisioned giant coastal “nuplexes” desalinating sea water; geostationary satellites powered by compact nuclear reactors for broadcasting TV programs; nuclear-powered tankers; and nuclear explosives that would alter the flow of rivers and excavate underground cities.

The promises of nuclear energy remained unfulfilled, because of stalled projects to generate electricity from fission (as demand for electricity fell in the 1980s), and other problems. Accidents like those at Three Mile Island (1979), Chernobyl (1986), and Fukushima (2011) provided further evidence for those opposed to fission. There are plenty of high costs outside planned budget in construction. The problem of finding an acceptable way for permanent storage of waste material has remained unsolved (the geologic storage facility in Finland is a world's first, see Tom Scott's video). This results in Western societies being reluctant to adopt nuclear energy. China and India are expanding. Things we could do are 1) using better reactor designs, and 2) acting on waste storage.

All the fossil fuels we need to get electricity from wind:

- Smelting of iron ore in a blast furnace for the production of steel.

- Naptha and gas for the synthesis of plastic and fiber glass.

- Diesel for ships, trucks, and construction machinery.

- Lubricant for gearboxes throughout the lifespan of a wind turbine.

Batteries are too small. There is a need for more compact, more flexible, larger-scall, less costly electricity storage. Li-ion batteries won't be sufficient in case a (mega)city is cut off from powerlines and needs to sustain for a few days on its own. Current solutions trying to address this, are large pumped hydro storage plants that basically pump water to a higher reservoir during night time (when electricity is cheap) to gain energy potential for periods of peak demand. Pumped storage accounts for more than ninety-nine percent of the world's storage capacity, but it has an inevitable energy loss around twenty-five percent. Many places also do not have mountains nearby to build such facilities.

Container ships are very hard to make electric. To have an electric ship whose batteries and motors weighed no more than the fuel and the diesel engine in today's largest container vessels (carrying 23,756 TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units)), we need batteries with an energy density more than ten times as high as today's best Li-ion units. In the past seventy years, the energy density hasn't even quadrupled.

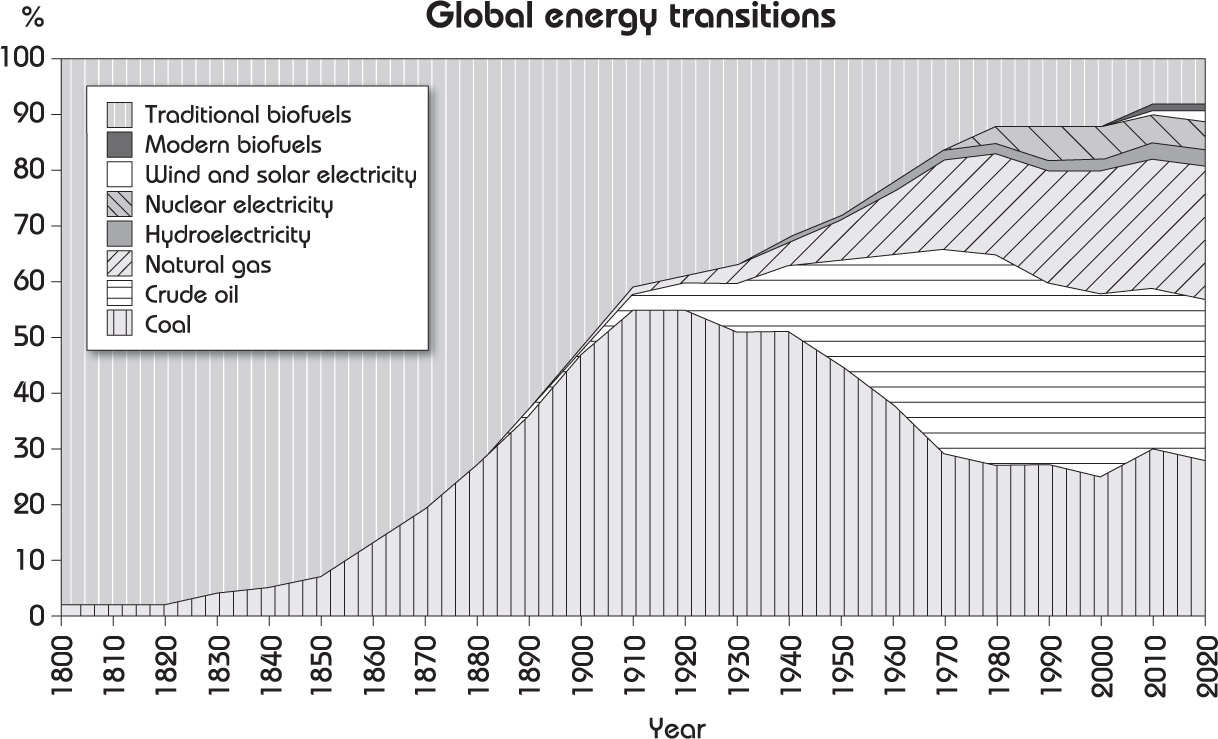

Graph depicting the global percentual breakdown of energy sources over the last two hundred years. Figure by Vaclav Smil.

Coal, crude oil, and natural gas together still account for nearly all global energy. This is somewhat depressing to me.

But solar and wind electricity generation are now mature industries, and new capacities can be added quickly—increasing the pace of decarbonizing the electricity supply. In contrast, several key economic sectors depend heavily on fossil fuels and we do not have any non-carbon alternatives that could replace them rapidly and on the requisite massive scales. These sectors include long-distance transportation (now almost totally reliant on aviation kerosene for jetliners, and diesel, bunker fuel, and liquefied natural gas for container, bulk, and tanker vessels); the production of more than a billion tons of primary iron (requiring coke made from coal for smelting iron ores in blast furnaces) and more than 4 billion tons of cement (made in massive rotating kilns fired by low-quality fossil fuels); the synthesis of nearly 200 million tons of ammonia and some 300 million tons of plastics (starting with compounds derived from natural gas and crude oil); and space heating (now dominated by natural gas).

Vaclav's conclusion:

These realities, rather than any wishful thinking, must guide our understanding of primary energy transitions. Displacing 10 billion tons of fossil carbon is a fundamentally different challenge than ramping up the sales of small portable electronic devices to more than a billion units a year; the latter feat was achieved in a matter of years, the former one is a task for many decades.